Three Marks of a Martyr

Back in college a few years ago, I wrote my History Senior Thesis paper on the distinctions between martyrdom and suicide in the pre-Augustinian Church. In that paper I discussed a semi-related view towards martyrdom that I had not found clearly stipulated in any source I had come in contact with so far. This view was that the early Church implicitly believed that true martyrs were marked by three characteristics: they believed in orthodox teachings, were hunted down (arrested, taken captive, pursued) for those beliefs, and were killed. A few days ago I finished reading an article, published only months after I began writing my paper, wherein a similar idea was presented. William Weinrich wrote about "a few simple observations."

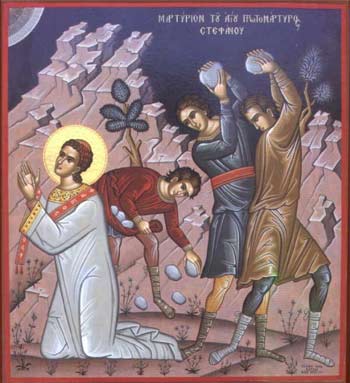

Martyrdom entails death; only that one who dies for the faith is called a "martyr" . . . the death imposed on the martyr is the result of a judgment to death.. . . the judgment to death imposed on the martyr is due to the refusal of the martyr to confess and to sacrifice to false gods. Confession of faith, rejection of idolatry, and judgment to death--these are the irreducible components of every martyrdom.1

These points are integral to understanding how the early Church viewed martyrs, and distinguished true martyrs from those who simply died. False martyrs were not respected at all.

As is touched on in the article, a perfect example of this idea is found in the Martyrdom of Polycarp. The writer first discussed the story of Quintus, a man who convinced several others to turn themselves into the authorities so they could achieve martyrdom. After some threatening and entreaties, the authorities were able to convince Quintus and his band to abjure and offer sacrifice to the Roman gods. In contrast, Polycarp ran (as is the directive of Christ2), was arrested, and was unshakable in his faith and confession. He the authorities were unable to break and force to offer a sacrifice.

Quintus would have been a false Christian martyr in the eyes of the early Church: "we do not commend those who give themselves up [to suffering], seeing the Gospel does not teach so to do."3 Not only did he and his group fail when they were tested, they volunteered their lives wanting to achieve martyrdom and receive the martyr's glory. Polycarp, in stark contrast, was pursued, arrested while fleeing, and held strongly to the faith he loved for so long. For that he met the martyr's fate. Polycarp's example shows all three above mentioned points. Quintus's fails in all respects.

We need to also understand Polycarp's example as it pertains to how we need to act if ever faced with true persecution. We must never just volunteer ourselves for death. Martyrdom is truly a calling of God, and only He can grant you the endurance and strength to be firm when the time comes. Flee from your persecutors, but never cease to confess the true faith. And never compromise the truth, especially for the sake of your own life. That last point I hope everyone can take to heart, even if you are never persecuted.

1 William C. Weinrich, "Death and Martyrdom: An Important Aspect of Early Christian Eschatology," Concordia Theological Quarterly, October 2002, 327-8.

2 Mt. x.21-23: "Brother will hand over brother to death, and a father his child. Children will rise against parents and have them put to death. And you will be hated by everyone because of my name. But the one who endures to the end will be saved. Whenever they persecute you in one place, flee to another."

3 Martyrdom of Polycarp, iv.

The two FOX News journalists kidnapped in Gaza on 14 August were released and spoke with their media brethren about their ordeal. During the interview they revealed the strong arm tactics their captors used to grant their release. From

The two FOX News journalists kidnapped in Gaza on 14 August were released and spoke with their media brethren about their ordeal. During the interview they revealed the strong arm tactics their captors used to grant their release. From  Then you have quite the dilemma that I have to work through almost on a daily basis in my studies on Christian martyrdom and persecution. What do you do with the

Then you have quite the dilemma that I have to work through almost on a daily basis in my studies on Christian martyrdom and persecution. What do you do with the  People also vary on on their attitude towards garnering freedom by any means in order to live on and preach the gospel of Christ versus denying Christ knowing death was an inevitable consequence. Some whole heartedly believe in doing everything you can to live. Living on and preaching the gospel or living the gospel is the most important thing to do. Saying words like "I deny Christ as God" or " Jesus is not God or my Savior" or "Yes I will embrace Allah and his prophet Muhammed" is nothing but words. As long as it is only a ruse then you are alright. Others will call such an act disgraceful and shameful towards Christ. How strong is your faith? Do you really believe Christ is God and able to take care of you? Is your life more important than the name of Christ?

People also vary on on their attitude towards garnering freedom by any means in order to live on and preach the gospel of Christ versus denying Christ knowing death was an inevitable consequence. Some whole heartedly believe in doing everything you can to live. Living on and preaching the gospel or living the gospel is the most important thing to do. Saying words like "I deny Christ as God" or " Jesus is not God or my Savior" or "Yes I will embrace Allah and his prophet Muhammed" is nothing but words. As long as it is only a ruse then you are alright. Others will call such an act disgraceful and shameful towards Christ. How strong is your faith? Do you really believe Christ is God and able to take care of you? Is your life more important than the name of Christ?